The efficacy and safety of nutrient supplements in the treatment of mental disorders: a meta‐review of meta‐analyses of randomized controlled trials

World Psychiatry https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20672

Joseph Firth Scott B. Teasdale Kelly Allott Dan Siskind Wolfgang Marx Jack Cotter Nicola Veronese Felipe Schuch Lee Smith … See all authors

Depression

- Vitamin D depression RCT canceled: too many were taking Vitamin D supplements, etc. Feb 2018

- Anti-depression medication about as good as big increase in vitamin D – meta-analysis of flawless data April 2014

- Reduced depression with single 300,000 IU injection of vitamin D – RCT June 2013

- Mood disorders 11X worse for older adults with low vitamin D – 2006

1 Vitamin D pill every two weeks fights all of the following

Diabetes + Heart Failure + Chronic Pain + Depression + Autism + Breast Cancer + Colon Cancer + Prostate Cancer + BPH (prostate) + Preeclampsia + Premature Birth + Falls + Cognitive Decline + Respiratory Tract Infection + Influenza + Tuberculosis + Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease + Lupus + Inflammatory Bowel Syndrome + Urinary Tract Infection + Poor Sleep + Growing Pain + Multiple Sclerosis + PMS + Schizophrenia + Endometriosis + Smoking 27 problems

Note: Once a week also fights: COVID, Headaches, Colds, Fibromyalgia, Asthma, Hives, Colitis etc.

Items in both categories Omega-3 and Depression are listed here

- Overweight needed more EPA (4 grams) to fight depression – RCT Aug 2022

- Anxiety, depression, and suicide have recently surged (Note: Vitamin D, Omega-3, and Magnesium help) – May 2022

- Omega-3 did not prevent depression (they failed to reduce Omega-6, which blocks Omega-3) – RCT Dec 2021

- Mental health not helped by vitamin D monotherapy (adding Omega-3 and Magnesium help) – review Nov 2021

- Benefits of Omega-3 plus Vitamin D were additive – RCT Sept 2021

- Depression treatments: diet, exercise, bright light, Vitamin D, B12, Omega-3, Zinc, Music, etc. – May 2019

- Omega-3 helps treat Major Depression – International Consensus Sept 2019

- Mental disorders fought by Omega-3 etc. - meta-meta-analysis Oct 2019

- Omega-3 reduces Depression. Anxiety, Stress, PTSD, etc. – Aug 2018

- Depression treated by Omega-3 (again) – meta-analysis Aug 2019

- Depression after childbirth 5 X less likely if good Omega-3 index – April 2019

- Occupational burnout reduced after 8 weeks of Omega-3 – RCT July 2019

- Anxiety severity reduced if more than 2 grams of Omega-3 – meta-analysis Sept 2018

- Psychotic disorders not treated by Omega-3 when patents take anti-depressants and get therapy – June 2018

- Happy Nurses Project gave Omega-3 for 3 months – reduced depression, insomnia, anxiety, etc for a year – RCT July 2018

- Depression – is it reduced by Vitamin D and or Omega-3 – RCT 2019

- Benefits of Omega-3 beyond heart health - LEF Feb 2018

- Omega-3 improves gut bacteria, reduces inflammation and depression – Dec 2017

- Unipolar depression treated by Omega-3, Zinc, and probably Vitamin D – meta-analysis Oct 2017

- Omega-3 reduces many psychiatric disorders – 2 reviews 2016

- Omega-3 does not consistently treat depression if use small amounts for short time period – review Oct 2016

- How Omega-3 Fights Depression – LEF July 2016

- Depression due to inflammation reduced by Omega-3 (children and pregnant) – Nov 2015

- Depression treated somewhat by Omega-3 (St. John's Wort better) – RAND org reviews 2015

- Depression substantially decreased with Omega-3 – Sept 2015

- Omega-3 for just 3 months greatly reduced psychosis for 80 months – RCT Aug 2015

- Omega-3 prevents PTSD and some mood disorders - Aug 2015

- Omega-3, Vitamin D, and other nutrients decrease mental health problems – March 2015

Intervention of Vitamin D for Depression

- Depression cost-effectively reduced by 50,000 IU of Vitamin D monthly (Iranian teens) – July 2023

- Infants getting an additional 800 IU of vitamin D for 2 years had 60% fewer psychiatric symptoms at age 7 – RCT May 2023

- Anxiety and Depression decreased in senior prediabetics with weekly 25,000 IU of Vitamin D – RCT Sept 2022

- Depression decreased by Vitamin D (12th study in VitaminDWiki) – RCT Nov 2022

- Overweight needed more EPA (4 grams) to fight depression – RCT Aug 2022

- Smoking depression, etc. reduced by Vitamin D (bi-weekly, 50,000 IU) - RCT Dec 2021

- Omega-3 did not prevent depression (they failed to reduce Omega-6, which blocks Omega-3) – RCT Dec 2021

- Weekly Vitamin D plus daily Magnesium is great (reduced depression in obese women in this case) – July 2021

- Depression in psychiatric youths reduced 28 percent after just 1 month of vitamin D – RCT Feb 2020

- Yet another study confirms Depression is treated by weekly Vitamin D (50,000 IU)– RCT Dec 2019

- Depression decreased after vitamin D (50,000 IU weekly to elderly in the case) – RCT Oct 2019

- Vitamin D - no cure for depression (when you use only 1200 IU) – Aug 2019

- Depression reduced in Diabetics with 3 months of 4,000 IU of vitamin D – RCT July 2019

- Vitamin D treatment of diabetes (50,000 IU every 2 weeks) augmented by probiotic – RCT June 2018

- Women had better sexual desire, orgasm and satisfaction after Vitamin D supplementation – Feb 2018

- Vitamin D depression RCT canceled: too many were taking Vitamin D supplements, etc. Feb 2018

- Depression in adolescent girls reduced somewhat by 50,000 IU weekly for 9 weeks – July 2017

- Perinatal depression decreased 40 percent with just a few weeks of 2,000 IU of vitamin D – RCT Aug 2016

- Just 1500 IU of Vitamin D significantly helps Prozac – RCT March 2013

- Reduced depression with single 300,000 IU injection of vitamin D – RCT June 2013

- 40,000 IU vitamin D weekly reduced depression in many obese subjects – RCT 2008

- 50,000 IU Vitamin D weekly Improves Mood, Lowers Blood Pressure in Type 2 Diabetics – Oct 2013

All Meta-analyses of Vitamin D and Depression

- Depression reduced by 8,000 IU of Vitamin D daily – meta-analysis Nov 2024

- Depression 1.6 X more likely if low Vitamin D, taking Vitamin D reduces depression – umbrella of meta-analyses – Jan 2023

- Depression in seniors greatly reduced by Vitamin D (50,000 IU weekly) – meta-analysis June 2023

- Depression reduced if take more than 5,000 IU of vitamin D daily – umbrella meta-analysis – Jan 2023

- Depression reduced if use more than 2,800 IU of vitamin D – meta-analysis Aug 2022

- Depression is treated by 2,000 IU of Vitamin D – 2 meta-analyses July 2022

- Depression treated by 50K IU Vitamin D weekly (but not 1,000 IU daily) – meta-analysis Jan 2021

- Mental disorders fought by Omega-3 etc. - meta-meta-analysis Oct 2019

- Depression less likely if more Vitamin D (12 percent per 10 ng) – meta-analysis July 2019

- Anxiety severity reduced if more than 2 grams of Omega-3 – meta-analysis Sept 2018

- Less depression in seniors taking enough Omega-3 – meta-analysis July 2018

- Unipolar depression treated by Omega-3, Zinc, and probably Vitamin D – meta-analysis Oct 2017

- Depression is associated with low Magnesium – meta-analysis April 2015

- Clinical Trials of vitamin D can have “biological flaws” – Jan 2015

- Slight depression not reduced by adding vitamin D if already had enough (no surprise) – meta-analysis – Nov 2014

- Anti-depression medication about as good as big increase in vitamin D – meta-analysis of flawless data April 2014

- Depression might be reduced by vitamin D – meta-analysis March 2014

- Low vitamin D and depression - Study and meta-analysis, April 2013

- 2X more likely to be depressed if low vitamin D (cohort studies) - Meta-analysis Jan 2013

Depression category listing has 271 items along with related searches

ADHD

ADHD and Omega-3 in VitaminDWiki

-

ADHD risk factors include low Zinc, Vitamin D, Magnesium and Omega-3 (umbrella review) – Oct 2020

-

Mental disorders fought by Omega-3 etc. - meta-meta-analysis Oct 2019

-

Behavior disorders reduced with Magnesium, Omega-3, and Zinc

-

ADHD children eat less fatty fish (Omega-3 again) – May 2019

-

Omega-3 probably can decrease Autism and ADHD – March 2019

-

Omega-3 reduced violence in children and violence between parents – RCT May 2018

-

ADHD, Autism, Early Psychosis and Omega-3 – review Dec 2017

-

ADHD 2 times more likely if poor Omega-6 to Omega-3 ratio – meta-analysis May 2016

-

ADHD and Vitamin D Deficiency

Bipolar

Biploar and Omega-3 in VitaminDWiki

Cognition

Cognition and Omega-3 in VitaminDWiki

-

Risk of Alzheimer’s is decreased by food, supplements, and lifestyle – Aug 2024

-

APOE-04 Alzheimer’s progression slowed up by Omega-3 – RCT Aug 2024

-

Dementia prevented by Omega-3, Vitamin D, etc. book and video May 2024

-

Better cognition associated with higher Omega-3 index – Sept 2023

-

Alzheimer’s delayed 4.7 years by high Omega-3 index (7.6 years if also have APOE-4) June - 2022

-

Dementia 4.1 X high risk in those with low Vitamin D, Omega-3, etc.2 decades before (behind paywall) – Nov 2021

-

Early brain development helped by Iron, Iodine, Vitamin D, Omega-3. Zinc etc. – Oct 2021

-

Omega-3 paused Alzheimer's decline - RCT Sept 2021

-

Seafood (Omega-3) during pregnancy increased childhood IQ by 8 points – review Dec 2019

-

Omega-3 index of 6 to 7 associated with best cognition in this study – Nov 2019

-

Eating fish improves cognition (Omega-3 fish during pregnancy in this case) - Oct 2019

-

Mental disorders fought by Omega-3 etc. - meta-meta-analysis Oct 2019

-

Omega-3 prevents Parkinson’s Disease – Review of RCT July 2019

-

Omega-3 helps brains of seniors – May 2019

-

Omega-3 helped Alzheimer’s only if good level of B vitamins – RCT April 2019

-

Standard Omega-3 not get past blood-brain barrier in seniors at high risk of Alzheimer’s – Patrick hypothesis Oct 2018

-

APOE4 gene problems (Alzheimer’s) reduced by both Vitamin D and Omega-3 - Dec 2018

-

Omega-3 is important for Brain Health during all phases of life – Aug 2018

-

Hypothesis: Omega-3 reduces Alzheimer’s directly and via the gut – Sept 2018

-

Improve Cognitive Health and Memory with Vitamin D and Omega-3 – World Patent March 2018

-

IQ levels around the world are falling (perhaps lower Vitamin D, Iodine, or Omega-3)

-

Adding Vitamin D, Omega-3, etc to children’s milk improved memory (yet again) – RCT June 2018

-

Omega-3, Vitamin D, Folic acid etc. during pregnancy and subsequent mental illness of child – March 2018

-

Why Alzheimer’s studies using Omega-3 have mixed results – quality, dose size, Omega-6, genes, etc. March 2018

-

Benefits of Omega-3 beyond heart health - LEF Feb 2018

-

Supplementation while pregnant and psychotic – 20 percent Omega-3, 6 percent Vitamin D – June 2016

-

ADHD, Autism, Early Psychosis and Omega-3 – review Dec 2017

-

Mild Traumatic Brain Injury prevented with Omega-3, Resveratrol, etc (in rats) – Oct 2017

-

Omega-3 found to treat Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s in animals – Sept 2017

-

The End of Alzheimer's and Dementia if adjust Vitamin D, B-12, Iron, Omega-3, etc.

-

Violent schizophrenia patients treated by 3 months of Omega-3 – RCT Aug 2017

-

Psychosis risk reduced for 80 weeks by just 12 weeks of Omega-3 – RCT Aug 2017

-

Alzheimer’s (apoE4) may require more than Omega-3 - May 2017

-

Infants getting 1 g of Omega-3 for 12 weeks got better brains – RCT March 2017

-

Omega-3 reduces many psychiatric disorders – 2 reviews 2016

-

Cognitive Impairment 1.8 times more likely if low Omega-3– Oct 2016

-

Omega-3 may treat schizophrenia

-

Benefits of Omega-3 on brain development

-

Omega-3 helps childhood cognition – meta-analysis April 2016

-

Football Brain injuries prevented by Omega-3 – RCT Jan 2016

-

Schizophrenia treated by 6 months of Omega-3 – RCT Nov 2015

-

Omega-3 and infant development - dissertation Sept 2015

-

Omega-3 etc improved both cognition and mobility of older women – Aug 2015

-

Schizophrenia relapses reduced 3X by Omega-3 – RCT Mar 2015

-

Cognitive decline in elderly slowed by Omega-3 – meta-analysis May 2015

-

Cognitively impaired brain atrophy was slowed 40 percent by Omega-3 and B vitamins – RCT July 2015

-

Omega-3, Vitamin D, and other nutrients decrease mental health problems – March 2015

-

Vitamin D, Omega-3 supplementation helps cognition – perhaps due to serotonin – Feb 2015

-

Vitamin D and Omega-3 may reduce cortical atrophy with age – Nov 2013

-

Alzheimer’s and Vitamins D, B, C, E, as well as Omega-3, metals, etc. – June 2013

This meta-meta was reviewed at GrassrootsHealth

Download the PDF from VitaminDWiki

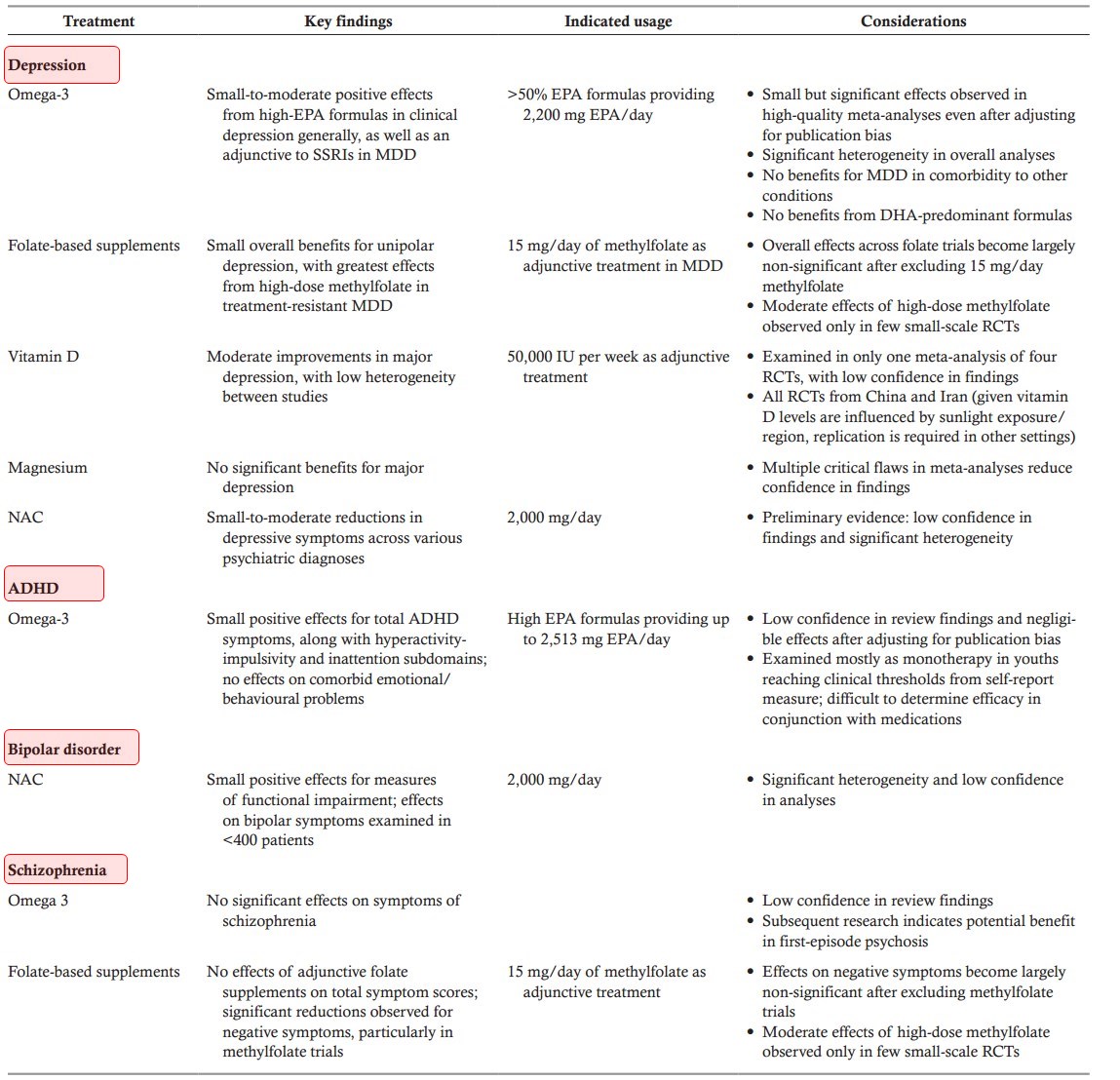

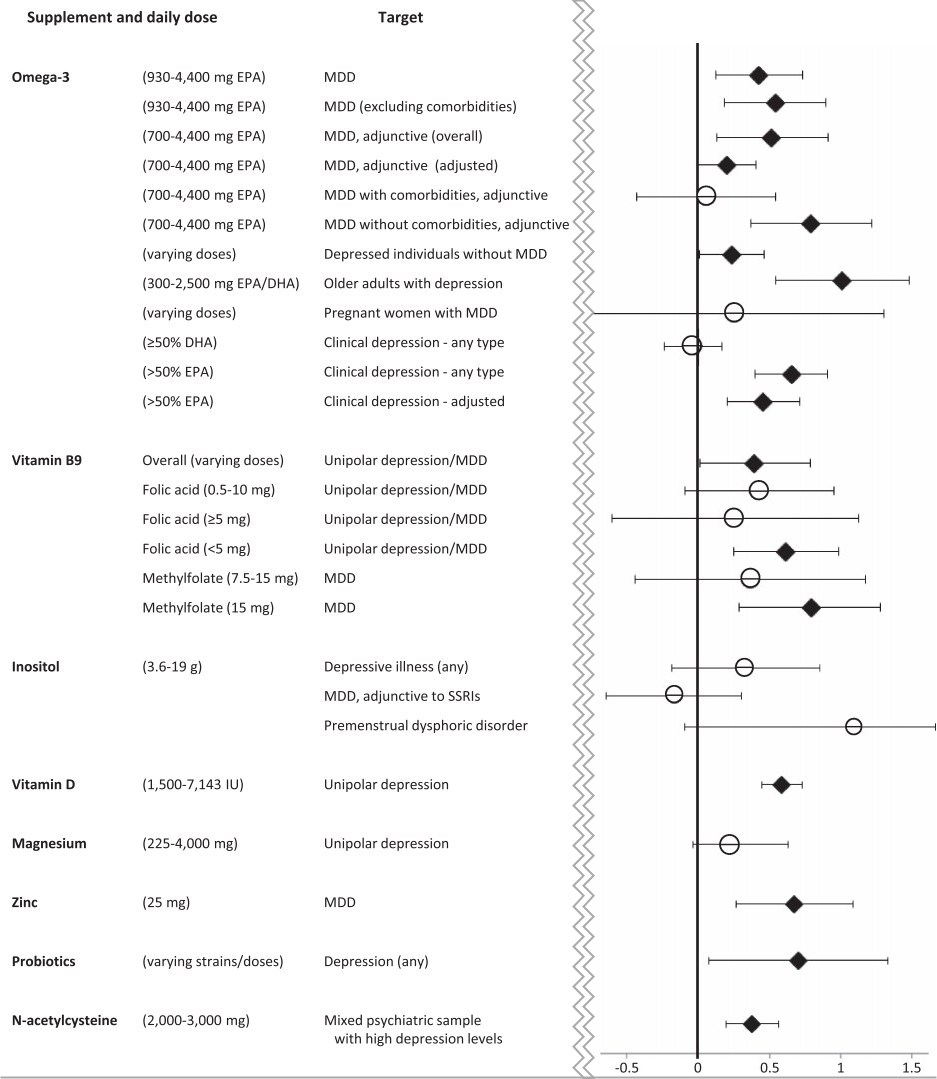

Depression

diamonds represent p ≤0.05 compared to placebo

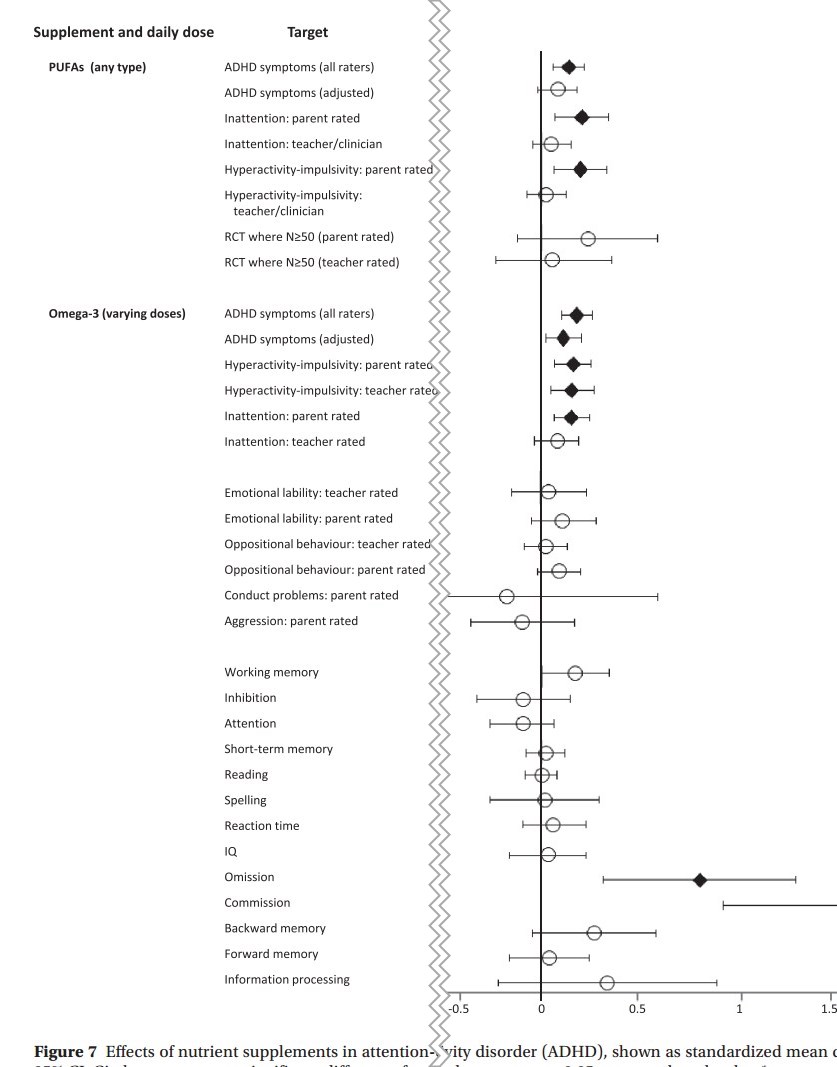

ADHD

diamonds represent p ≤0.05 compared to placebo

The role of nutrition in mental health is becoming increasingly acknowledged. Along with dietary intake, nutrition can also be obtained from “nutrient supplements”, such as polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), vitamins, minerals, antioxidants, amino acids and pre/probiotic supplements. Recently, a large number of meta‐analyses have emerged examining nutrient supplements in the treatment of mental disorders. To produce a meta‐review of this top‐tier evidence, we identified, synthesized and appraised all meta‐analyses of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) reporting on the efficacy and safety of nutrient supplements in common and severe mental disorders. Our systematic search identified 33 meta‐analyses of placebo‐controlled RCTs, with primary analyses including outcome data from 10,951 individuals. The strongest evidence was found for PUFAs (particularly as eicosapentaenoic acid) as an adjunctive treatment for depression. More nascent evidence suggested that PUFAs may also be beneficial for attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder, whereas there was no evidence for schizophrenia. Folate‐based supplements were widely researched as adjunctive treatments for depression and schizophrenia, with positive effects from RCTs of high‐dose methylfolate in major depressive disorder. There was emergent evidence for N‐acetylcysteine as a useful adjunctive treatment in mood disorders and schizophrenia. All nutrient supplements had good safety profiles, with no evidence of serious adverse effects or contraindications with psychiatric medications. In conclusion, clinicians should be informed of the nutrient supplements with established efficacy for certain conditions (such as eicosapentaenoic acid in depression), but also made aware of those currently lacking evidentiary support. Future research should aim to determine which individuals may benefit most from evidence‐based supplements, to further elucidate the underlying mechanisms.

DISCUSSION

This meta‐review aggregated and evaluated all the recent top‐tier evidence from meta‐analyses of RCTs examining the efficacy and safety of nutritional supplements in mental disorders. We identified 33 eligible meta‐analyses published from 2012 onwards (26 since 2016), with primary analyses including 10,951 individuals with psychiatric conditions (specifically depressive disorders, anxiety and stress‐related disorders, schizophrenia, states at risk for psychosis, bipolar disorder and ADHD), randomized to either nutritional supplementation (including omega‐3 fatty acids, vitamins, minerals, N‐acetylcysteine and other amino acids) or placebo control conditions. Although the majority of nutritional supplements assessed did not significantly improve mental health outcomes beyond control conditions (see Figures 2-7), some of them did provide efficacious adjunctive treatment for specific mental disorders under certain conditions.

The nutritional intervention with the strongest evidentiary support is omega‐3, in particular EPA. Multiple meta‐analyses have demonstrated that it has significant effects in people with depression, including high‐quality meta‐analyses with good confidence in findings as determined by AMSTAR‐264. Meta‐analytic data have shown that omega‐3 is effective when given adjunctively to antidepressants51, 64. As a monotherapy intervention, the data are less compelling for omega‐3, while DHA or DHA‐predominant formulas do not appear to show any obvious benefit in MDD51, 64.

Omega‐3 supplementation appears to be of greatest benefit when administered as high‐EPA formulas, as significant relationships between EPA dosage and effect sizes are also observed in high‐quality meta‐analyses of RCTs59, 64. Emergent data from RCTs further indicate that omega‐3 may be most beneficial for patients presenting with raised inflammatory markers83. The available meta‐analyses suggest that omega‐3 supplementation is not effective in patients with depression as a comorbidity to chronic physical conditions65, including cardiometabolic diseases, a finding which has been replicated in subsequent trials84. In light of current adverse event data, omega‐3 seems to represent a safe adjunctive treatment.

More research is needed concerning the efficacy of omega‐3 supplements in other mental health conditions. For instance, omega‐3 was indicated as potentially beneficial for children with ADHD, again with high EPA formulas conferring largest effects79. However, the negligible effect sizes after controlling for publication bias, along with the low review quality identified by AMSTAR‐2, reduces confidence in findings. Additionally, whereas the existing meta‐analytic data have found a lack of significant benefits in people with schizophrenia55, 59, subsequent trials in young people with first‐episode psychosis have reported more positive, though mixed, results85, 86, putatively ascribed to neuroprotective effects87, 88.

Adjunctive treatment with folate‐based supplements was found to significantly reduce symptoms of MDD and negative symptoms in schizophrenia54, 67. However, in both cases, AMSTAR‐2 ratings indicated low confidence in review findings, and positive overall effects in these meta‐analyses were driven largely by RCTs of high‐dose (15 mg/day) methylfolate. Methylfolate is readily absorbed, overcoming any genetic predispositions towards folic acid malabsorption, and successfully crossing the blood‐brain barrier89, 90. Indeed, a placebo‐controlled trial of methylfolate in schizophrenia reported significant increases in white matter within just 12 weeks, co‐occurring with a reduction in negative symptoms91.

RCTs not captured in our meta‐review92 and retrospective chart analyses93 have further indicated benefits of methylfolate supplementation in other mental disorders. Considering this, alongside the lack of detrimental side effects (in fact, significantly fewer adverse events in samples receiving treatment compared to placebo54), further research on methylfolate as an adjunctive treatment for mental disorders is warranted.

Regarding other vitamins (such as vitamin E, C or D), minerals (zinc and magnesium) or inositol, there is currently a lack of compelling evidence supporting their efficacy for any mental disorder, although the emerging evidence concerning positive effects for vitamin D supplementation in major depression has to be mentioned.

Beyond vitamins, minerals and omega‐3 fatty acids, certain amino acids are now emerging as promising adjunctive treatments in mental disorders. Although the evidence is still nascent, N‐acetylcysteine in particular (at doses of 2,000 mg/day or higher) was indicated as potentially effective for reducing depressive symptoms and improving functional recovery in mixed psychiatric samples72. Furthermore, significant reductions in total symptoms of schizophrenia have been observed when using N‐acetylcysteine as an adjunctive treatment, although with substantial heterogeneity between studies, especially in study length (in fact, N‐acetylcysteine has a very delayed onset of action of about 6 months56, 94).

N‐acetylcysteine acts as a precursor to glutathione, the primary endogenous antioxidant, neutralizing cellular reactive oxygen and nitrogen 95. Glutathione production in astrocytes is rate limited by cysteine. Oral glutathione and L‐cysteine are broken down by first‐pass metabolism, and do not increase brain glutathione levels, unlike oral N‐acetylcysteine, which is more easily absorbed, and has been shown to increase brain glutathione in animal models96. Additionally, N‐acetylcysteine has been shown to increase dopamine release in animal models96.

N‐acetylcysteine may assist in treatment of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and depression through decreasing oxidative stress and reducing glutamatergic dysfunction96, but has wider preclinical effects on mitochondria, apoptosis, neurogenesis and telomere lengthening of uncertain clinical significance.

NMDA receptors are activated by binding D‐serine or glycine97. Sarcosine is a naturally occurring glycine transport inhibitor and can act as a co‐agonist of NMDA98. As such, D‐serine, glycine and sarcosine may improve psychotic symptoms through NDMA modulation99. We found reductions in total psychotic symptoms, but not negative symptoms, with glycine and sarcosine. Additionally, we found that glycine was not effective in combination with clozapine. This may be because clozapine already acts as a NMDA receptor glycine site agonist97.

The role of the gut microbiome in mental health is also a rapidly emerging field of research99. Gut microbiota differs significantly between people with mental disorders and healthy controls, and recent faecal transplant studies using germ‐free mice indicate that these differences could play a causal role in symptoms of mental illness41, 100, 101. Intervention trials that aim to investigate the effect of probiotic formulations on clinical outcomes in mental disorders are now beginning to emerge71. We included one recent meta‐analysis that evaluated the pooled effect of probiotic interventions on depressive symptoms: while the primary analysis reported no significant effect, the moderately large effect in the three included studies suggests that probiotics may be beneficial for those with a clinical diagnosis of depression rather than subclinical symptoms71. However, additional trials are required to replicate these results, to evaluate the long‐term safety of probiotic interventions, and to elucidate the optimal dosing regimen and the most effective prebiotic and probiotic strains102.

While this meta‐review has highlighted potential roles for the use of nutrient supplements, this should not be intended to replace dietary improvement. The poor physical health of people with mental illness is well documented103, and excessive and unhealthy dietary intake appears to be a key factor involved4, 5. Improved diet quality is associated with reduced all‐cause mortality104. whereas multivitamin and multimineral supplements may not improve life expectancy18-20.

A meta‐analysis of dietary interventions in people with severe mental illness found benefits on a number of physical health aspects105. It is unlikely that standard nutrient supplementation will be able to cover all beneficial aspects of improved dietary intake. In addition, whole foods may contain vitamins and minerals in different forms, whereas nutrient supplements may only provide one form. For example, vitamin E occurs naturally in eight forms, but nutrient supplements may only provide one form. Dietary interventions also reduce dietary elements in excess, such as salt, which is a key driver of premature mortality13.

While improving dietary intake appears to have a clear role in increasing life expectancy and preventing chronic disease, there is currently a lack of studies evaluating this in people with mental disorders. Additionally, although recent meta‐analyses of RCTs have demonstrated that dietary improvement reduces symptoms of depression in the general population106, more well‐designed studies are needed to confirm the mental health benefits of dietary interventions for people with diagnosed psychiatric conditions25.

Our data should be considered in the light of some limitations. First, although meta‐analyses of RCTs typically constitute the top‐tier of evidence, it is important to acknowledge that many of the outcomes included in this meta‐review had significant amounts of heterogeneity between the included studies, or were based on a small number of studies. A next step within this field of research is to move from study‐level to patient‐level meta‐analyses, as this would provide a more personalized picture of the effects of nutrient supplements derived from adequately powered moderator, mediator and subgroup analyses. Additionally, comparing nutrient supplements in the same trial would be desirable.

It is recognized that people with mental disorders commonly take nutritional supplements in combinations. In some instances, research has supported this approach, most commonly in the form of multivitamin/mineral combinations107. However, recent research in the area of depression has revealed that “more is not necessarily better” when it comes to complex formulations108. Of note, recent large mood disorder clinical trials have revealed that nutrient combinations may not have a more potent effect, and in some cases placebo has been more effective47, 108, 109.

In conclusion, there is now a vast body of research examining the efficacy of nutrient supplementation in people with mental disorders, with some nutrients now having demonstrated efficacy under specific conditions, and others with increasingly indicated potential. There is a great need to determine the mechanisms involved, along with examining the effects in specific populations such as young people and those in early stages of illness. A targeted approach is clearly warranted, which may manifest as biomarker‐guided treatment, based on key nutrient levels, inflammatory markers, and pharmacogenomics 83, 91, 110.

Mental disorders fought by Omega-3 etc. - meta-meta-analysis Oct 2019

11397 visitors, last modified 17 Jul, 2023,

Printer Friendly

Follow this page for updates

This page is in the following categories (# of items in each category)

Attached files

ID

Name

Uploaded

Size

Downloads

12635

Depression.jpg

admin 13 Sep, 2019

136.53 Kb

887

12634

ADHD.jpg

admin 13 Sep, 2019

104.42 Kb

913

12633

MD summary.jpg

admin 13 Sep, 2019

263.75 Kb

940

12632

Mental Disorders meta-analysis.pdf

admin 13 Sep, 2019

2.26 Mb

718

ADHD

ADHD and Omega-3 in VitaminDWiki

- ADHD risk factors include low Zinc, Vitamin D, Magnesium and Omega-3 (umbrella review) – Oct 2020

- Mental disorders fought by Omega-3 etc. - meta-meta-analysis Oct 2019

- Behavior disorders reduced with Magnesium, Omega-3, and Zinc

- ADHD children eat less fatty fish (Omega-3 again) – May 2019

- Omega-3 probably can decrease Autism and ADHD – March 2019

- Omega-3 reduced violence in children and violence between parents – RCT May 2018

- ADHD, Autism, Early Psychosis and Omega-3 – review Dec 2017

- ADHD 2 times more likely if poor Omega-6 to Omega-3 ratio – meta-analysis May 2016

- ADHD and Vitamin D Deficiency

Bipolar

Biploar and Omega-3 in VitaminDWiki

Cognition

Cognition and Omega-3 in VitaminDWiki

- Risk of Alzheimer’s is decreased by food, supplements, and lifestyle – Aug 2024

- APOE-04 Alzheimer’s progression slowed up by Omega-3 – RCT Aug 2024

- Dementia prevented by Omega-3, Vitamin D, etc. book and video May 2024

- Better cognition associated with higher Omega-3 index – Sept 2023

- Alzheimer’s delayed 4.7 years by high Omega-3 index (7.6 years if also have APOE-4) June - 2022

- Dementia 4.1 X high risk in those with low Vitamin D, Omega-3, etc.2 decades before (behind paywall) – Nov 2021

- Early brain development helped by Iron, Iodine, Vitamin D, Omega-3. Zinc etc. – Oct 2021

- Omega-3 paused Alzheimer's decline - RCT Sept 2021

- Seafood (Omega-3) during pregnancy increased childhood IQ by 8 points – review Dec 2019

- Omega-3 index of 6 to 7 associated with best cognition in this study – Nov 2019

- Eating fish improves cognition (Omega-3 fish during pregnancy in this case) - Oct 2019

- Mental disorders fought by Omega-3 etc. - meta-meta-analysis Oct 2019

- Omega-3 prevents Parkinson’s Disease – Review of RCT July 2019

- Omega-3 helps brains of seniors – May 2019

- Omega-3 helped Alzheimer’s only if good level of B vitamins – RCT April 2019

- Standard Omega-3 not get past blood-brain barrier in seniors at high risk of Alzheimer’s – Patrick hypothesis Oct 2018

- APOE4 gene problems (Alzheimer’s) reduced by both Vitamin D and Omega-3 - Dec 2018

- Omega-3 is important for Brain Health during all phases of life – Aug 2018

- Hypothesis: Omega-3 reduces Alzheimer’s directly and via the gut – Sept 2018

- Improve Cognitive Health and Memory with Vitamin D and Omega-3 – World Patent March 2018

- IQ levels around the world are falling (perhaps lower Vitamin D, Iodine, or Omega-3)

- Adding Vitamin D, Omega-3, etc to children’s milk improved memory (yet again) – RCT June 2018

- Omega-3, Vitamin D, Folic acid etc. during pregnancy and subsequent mental illness of child – March 2018

- Why Alzheimer’s studies using Omega-3 have mixed results – quality, dose size, Omega-6, genes, etc. March 2018

- Benefits of Omega-3 beyond heart health - LEF Feb 2018

- Supplementation while pregnant and psychotic – 20 percent Omega-3, 6 percent Vitamin D – June 2016

- ADHD, Autism, Early Psychosis and Omega-3 – review Dec 2017

- Mild Traumatic Brain Injury prevented with Omega-3, Resveratrol, etc (in rats) – Oct 2017

- Omega-3 found to treat Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s in animals – Sept 2017

- The End of Alzheimer's and Dementia if adjust Vitamin D, B-12, Iron, Omega-3, etc.

- Violent schizophrenia patients treated by 3 months of Omega-3 – RCT Aug 2017

- Psychosis risk reduced for 80 weeks by just 12 weeks of Omega-3 – RCT Aug 2017

- Alzheimer’s (apoE4) may require more than Omega-3 - May 2017

- Infants getting 1 g of Omega-3 for 12 weeks got better brains – RCT March 2017

- Omega-3 reduces many psychiatric disorders – 2 reviews 2016

- Cognitive Impairment 1.8 times more likely if low Omega-3– Oct 2016

- Omega-3 may treat schizophrenia

- Benefits of Omega-3 on brain development

- Omega-3 helps childhood cognition – meta-analysis April 2016

- Football Brain injuries prevented by Omega-3 – RCT Jan 2016

- Schizophrenia treated by 6 months of Omega-3 – RCT Nov 2015

- Omega-3 and infant development - dissertation Sept 2015

- Omega-3 etc improved both cognition and mobility of older women – Aug 2015

- Schizophrenia relapses reduced 3X by Omega-3 – RCT Mar 2015

- Cognitive decline in elderly slowed by Omega-3 – meta-analysis May 2015

- Cognitively impaired brain atrophy was slowed 40 percent by Omega-3 and B vitamins – RCT July 2015

- Omega-3, Vitamin D, and other nutrients decrease mental health problems – March 2015

- Vitamin D, Omega-3 supplementation helps cognition – perhaps due to serotonin – Feb 2015

- Vitamin D and Omega-3 may reduce cortical atrophy with age – Nov 2013

- Alzheimer’s and Vitamins D, B, C, E, as well as Omega-3, metals, etc. – June 2013

This meta-meta was reviewed at GrassrootsHealth

Download the PDF from VitaminDWiki

Depression

diamonds represent p ≤0.05 compared to placebo

ADHD

diamonds represent p ≤0.05 compared to placebo

The role of nutrition in mental health is becoming increasingly acknowledged. Along with dietary intake, nutrition can also be obtained from “nutrient supplements”, such as polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), vitamins, minerals, antioxidants, amino acids and pre/probiotic supplements. Recently, a large number of meta‐analyses have emerged examining nutrient supplements in the treatment of mental disorders. To produce a meta‐review of this top‐tier evidence, we identified, synthesized and appraised all meta‐analyses of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) reporting on the efficacy and safety of nutrient supplements in common and severe mental disorders. Our systematic search identified 33 meta‐analyses of placebo‐controlled RCTs, with primary analyses including outcome data from 10,951 individuals. The strongest evidence was found for PUFAs (particularly as eicosapentaenoic acid) as an adjunctive treatment for depression. More nascent evidence suggested that PUFAs may also be beneficial for attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder, whereas there was no evidence for schizophrenia. Folate‐based supplements were widely researched as adjunctive treatments for depression and schizophrenia, with positive effects from RCTs of high‐dose methylfolate in major depressive disorder. There was emergent evidence for N‐acetylcysteine as a useful adjunctive treatment in mood disorders and schizophrenia. All nutrient supplements had good safety profiles, with no evidence of serious adverse effects or contraindications with psychiatric medications. In conclusion, clinicians should be informed of the nutrient supplements with established efficacy for certain conditions (such as eicosapentaenoic acid in depression), but also made aware of those currently lacking evidentiary support. Future research should aim to determine which individuals may benefit most from evidence‐based supplements, to further elucidate the underlying mechanisms.

DISCUSSION

This meta‐review aggregated and evaluated all the recent top‐tier evidence from meta‐analyses of RCTs examining the efficacy and safety of nutritional supplements in mental disorders. We identified 33 eligible meta‐analyses published from 2012 onwards (26 since 2016), with primary analyses including 10,951 individuals with psychiatric conditions (specifically depressive disorders, anxiety and stress‐related disorders, schizophrenia, states at risk for psychosis, bipolar disorder and ADHD), randomized to either nutritional supplementation (including omega‐3 fatty acids, vitamins, minerals, N‐acetylcysteine and other amino acids) or placebo control conditions. Although the majority of nutritional supplements assessed did not significantly improve mental health outcomes beyond control conditions (see Figures 2-7), some of them did provide efficacious adjunctive treatment for specific mental disorders under certain conditions.

The nutritional intervention with the strongest evidentiary support is omega‐3, in particular EPA. Multiple meta‐analyses have demonstrated that it has significant effects in people with depression, including high‐quality meta‐analyses with good confidence in findings as determined by AMSTAR‐264. Meta‐analytic data have shown that omega‐3 is effective when given adjunctively to antidepressants51, 64. As a monotherapy intervention, the data are less compelling for omega‐3, while DHA or DHA‐predominant formulas do not appear to show any obvious benefit in MDD51, 64.

Omega‐3 supplementation appears to be of greatest benefit when administered as high‐EPA formulas, as significant relationships between EPA dosage and effect sizes are also observed in high‐quality meta‐analyses of RCTs59, 64. Emergent data from RCTs further indicate that omega‐3 may be most beneficial for patients presenting with raised inflammatory markers83. The available meta‐analyses suggest that omega‐3 supplementation is not effective in patients with depression as a comorbidity to chronic physical conditions65, including cardiometabolic diseases, a finding which has been replicated in subsequent trials84. In light of current adverse event data, omega‐3 seems to represent a safe adjunctive treatment.

More research is needed concerning the efficacy of omega‐3 supplements in other mental health conditions. For instance, omega‐3 was indicated as potentially beneficial for children with ADHD, again with high EPA formulas conferring largest effects79. However, the negligible effect sizes after controlling for publication bias, along with the low review quality identified by AMSTAR‐2, reduces confidence in findings. Additionally, whereas the existing meta‐analytic data have found a lack of significant benefits in people with schizophrenia55, 59, subsequent trials in young people with first‐episode psychosis have reported more positive, though mixed, results85, 86, putatively ascribed to neuroprotective effects87, 88.

Adjunctive treatment with folate‐based supplements was found to significantly reduce symptoms of MDD and negative symptoms in schizophrenia54, 67. However, in both cases, AMSTAR‐2 ratings indicated low confidence in review findings, and positive overall effects in these meta‐analyses were driven largely by RCTs of high‐dose (15 mg/day) methylfolate. Methylfolate is readily absorbed, overcoming any genetic predispositions towards folic acid malabsorption, and successfully crossing the blood‐brain barrier89, 90. Indeed, a placebo‐controlled trial of methylfolate in schizophrenia reported significant increases in white matter within just 12 weeks, co‐occurring with a reduction in negative symptoms91.

RCTs not captured in our meta‐review92 and retrospective chart analyses93 have further indicated benefits of methylfolate supplementation in other mental disorders. Considering this, alongside the lack of detrimental side effects (in fact, significantly fewer adverse events in samples receiving treatment compared to placebo54), further research on methylfolate as an adjunctive treatment for mental disorders is warranted.

Regarding other vitamins (such as vitamin E, C or D), minerals (zinc and magnesium) or inositol, there is currently a lack of compelling evidence supporting their efficacy for any mental disorder, although the emerging evidence concerning positive effects for vitamin D supplementation in major depression has to be mentioned.

Beyond vitamins, minerals and omega‐3 fatty acids, certain amino acids are now emerging as promising adjunctive treatments in mental disorders. Although the evidence is still nascent, N‐acetylcysteine in particular (at doses of 2,000 mg/day or higher) was indicated as potentially effective for reducing depressive symptoms and improving functional recovery in mixed psychiatric samples72. Furthermore, significant reductions in total symptoms of schizophrenia have been observed when using N‐acetylcysteine as an adjunctive treatment, although with substantial heterogeneity between studies, especially in study length (in fact, N‐acetylcysteine has a very delayed onset of action of about 6 months56, 94).

N‐acetylcysteine acts as a precursor to glutathione, the primary endogenous antioxidant, neutralizing cellular reactive oxygen and nitrogen 95. Glutathione production in astrocytes is rate limited by cysteine. Oral glutathione and L‐cysteine are broken down by first‐pass metabolism, and do not increase brain glutathione levels, unlike oral N‐acetylcysteine, which is more easily absorbed, and has been shown to increase brain glutathione in animal models96. Additionally, N‐acetylcysteine has been shown to increase dopamine release in animal models96.

N‐acetylcysteine may assist in treatment of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and depression through decreasing oxidative stress and reducing glutamatergic dysfunction96, but has wider preclinical effects on mitochondria, apoptosis, neurogenesis and telomere lengthening of uncertain clinical significance.

NMDA receptors are activated by binding D‐serine or glycine97. Sarcosine is a naturally occurring glycine transport inhibitor and can act as a co‐agonist of NMDA98. As such, D‐serine, glycine and sarcosine may improve psychotic symptoms through NDMA modulation99. We found reductions in total psychotic symptoms, but not negative symptoms, with glycine and sarcosine. Additionally, we found that glycine was not effective in combination with clozapine. This may be because clozapine already acts as a NMDA receptor glycine site agonist97.

The role of the gut microbiome in mental health is also a rapidly emerging field of research99. Gut microbiota differs significantly between people with mental disorders and healthy controls, and recent faecal transplant studies using germ‐free mice indicate that these differences could play a causal role in symptoms of mental illness41, 100, 101. Intervention trials that aim to investigate the effect of probiotic formulations on clinical outcomes in mental disorders are now beginning to emerge71. We included one recent meta‐analysis that evaluated the pooled effect of probiotic interventions on depressive symptoms: while the primary analysis reported no significant effect, the moderately large effect in the three included studies suggests that probiotics may be beneficial for those with a clinical diagnosis of depression rather than subclinical symptoms71. However, additional trials are required to replicate these results, to evaluate the long‐term safety of probiotic interventions, and to elucidate the optimal dosing regimen and the most effective prebiotic and probiotic strains102.

While this meta‐review has highlighted potential roles for the use of nutrient supplements, this should not be intended to replace dietary improvement. The poor physical health of people with mental illness is well documented103, and excessive and unhealthy dietary intake appears to be a key factor involved4, 5. Improved diet quality is associated with reduced all‐cause mortality104. whereas multivitamin and multimineral supplements may not improve life expectancy18-20.

A meta‐analysis of dietary interventions in people with severe mental illness found benefits on a number of physical health aspects105. It is unlikely that standard nutrient supplementation will be able to cover all beneficial aspects of improved dietary intake. In addition, whole foods may contain vitamins and minerals in different forms, whereas nutrient supplements may only provide one form. For example, vitamin E occurs naturally in eight forms, but nutrient supplements may only provide one form. Dietary interventions also reduce dietary elements in excess, such as salt, which is a key driver of premature mortality13.

While improving dietary intake appears to have a clear role in increasing life expectancy and preventing chronic disease, there is currently a lack of studies evaluating this in people with mental disorders. Additionally, although recent meta‐analyses of RCTs have demonstrated that dietary improvement reduces symptoms of depression in the general population106, more well‐designed studies are needed to confirm the mental health benefits of dietary interventions for people with diagnosed psychiatric conditions25.

Our data should be considered in the light of some limitations. First, although meta‐analyses of RCTs typically constitute the top‐tier of evidence, it is important to acknowledge that many of the outcomes included in this meta‐review had significant amounts of heterogeneity between the included studies, or were based on a small number of studies. A next step within this field of research is to move from study‐level to patient‐level meta‐analyses, as this would provide a more personalized picture of the effects of nutrient supplements derived from adequately powered moderator, mediator and subgroup analyses. Additionally, comparing nutrient supplements in the same trial would be desirable.

It is recognized that people with mental disorders commonly take nutritional supplements in combinations. In some instances, research has supported this approach, most commonly in the form of multivitamin/mineral combinations107. However, recent research in the area of depression has revealed that “more is not necessarily better” when it comes to complex formulations108. Of note, recent large mood disorder clinical trials have revealed that nutrient combinations may not have a more potent effect, and in some cases placebo has been more effective47, 108, 109.

In conclusion, there is now a vast body of research examining the efficacy of nutrient supplementation in people with mental disorders, with some nutrients now having demonstrated efficacy under specific conditions, and others with increasingly indicated potential. There is a great need to determine the mechanisms involved, along with examining the effects in specific populations such as young people and those in early stages of illness. A targeted approach is clearly warranted, which may manifest as biomarker‐guided treatment, based on key nutrient levels, inflammatory markers, and pharmacogenomics 83, 91, 110.

| 11397 visitors, last modified 17 Jul, 2023, |

| ID | Name | Uploaded | Size | Downloads | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12635 | Depression.jpg | admin 13 Sep, 2019 | 136.53 Kb | 887 | |

| 12634 | ADHD.jpg | admin 13 Sep, 2019 | 104.42 Kb | 913 | |

| 12633 | MD summary.jpg | admin 13 Sep, 2019 | 263.75 Kb | 940 | |

| 12632 | Mental Disorders meta-analysis.pdf | admin 13 Sep, 2019 | 2.26 Mb | 718 |